Corruption scandals that shook the world

In the wake of many of these scandals, many governments and international bodies committed to or implemented anti-corruption reforms, counted and, in some cases, recovered losses.

Over the past few decades several harrowing tales of corruption have rocked the both governments and the corporate world alike.

The Transparency International has compiled a list of some of the biggest corruption scandals over the last 25 years that inspired widespread public condemnation, toppled governments and sent people to prison.

These scandals involve politicians across political parties and from the highest reaches of government, staggering amounts of bribes and money laundering of epic proportions.

In the wake of many of these scandals, many governments and international bodies committed to or implemented anti-corruption reforms, counted and, in some cases, recovered losses.

While much progress has been made to improve accountability, raise awareness about how corruption happens and change norms and perceptions, we still have a long way to go to learn from these scandals and fight corruption effectively.

1. SIEMENS: CORRUPTION MADE IN GERMANY

Ten years ago a colossal corruption scandal involving Siemens, one of the world’s largest electrical engineering companies, shocked the world. The scale of it marked it out as the biggest corruption case of the time.

A few years later, Linda Thomsen, Director at the Security Exchange Commission described the pattern of bribery in the company as: "Unprecedented in scale and geographic reach. The corruption involved more than $1.4 billion in bribes to government officials in Asia, Africa, Europe, the Middle East and the Americas."

How did it happen and why is it important to keep this case in mind?

Prior to the corruption scandal, the reputation of Siemens was extremely good. It was renowned for its technological products and reliable services in telecommunications, power, transportation and medical equipment.

It was common to see articles featuring its activities in remote areas, developing new high quality products and winning competitive bids.

The reality was completely different.

Since at least the 1990s, Siemens had organised a global system of corruption to gain market share and increase its price. It was able to get away with this because of big loopholes in the legal systems of a host of countries, including Germany.

Time for justice

On July 5th 2000, Siemens issued a new corporate circular requiring operating groups and regional companies to ensure that a new anti-corruption clause would be included in all contracts with agents, consultants, brokers, or other third parties.

The following year it issued new guidelines that stipulated: "No employee may directly or indirectly offer or grant unjustified advantages to others in connection with business dealings, neither in monetary form nor as some other advantage."

In reality, as a German prosecutor was to comment later, the Siemens compliance programme existed only on paper.

But, as American prosecutors discovered: "Siemens management failed to adequately investigate or follow up on any of these issues."

All over the word – from Bangladesh, Vietnam, Russia, and Mexico to Greece, Norway Iraq and Nigeria – Siemens paid bribes to government officials and civil servants.

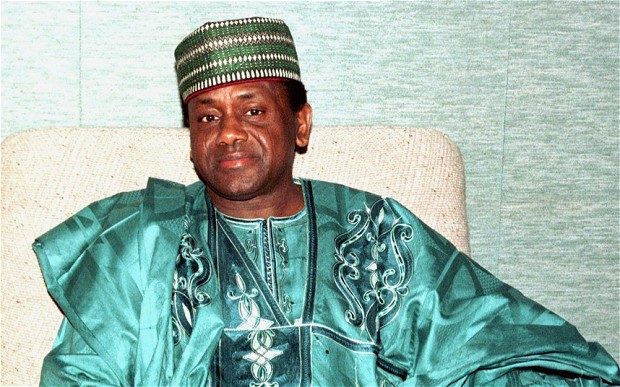

2. DRAINING NIGERIA OF ITS ASSETS

Sani Abacha was a Nigerian army officer and dictator who served as the president of Nigeria from 1993 until his death in 1998.

His five-year rule was shrouded in corruption allegations, though the extent and severity of that corruption was highlighted only after his death when it emerged that he took between US$3 and $5 billion of public money.

In 2014, the US Justice Department revealed that it froze more than US$458 million in illicit funds that Abacha and his conspirators hid around the world.

After a five-year court saga Jersey announced it was putting $268 million, which had been stashed in a Deutsche Bank account on the island by Sani Abacha, into an asset recovery fund that will eventually return the cash to Nigeria. The island’s solicitor general said the move showed “Jersey’s determination to deal with international financial crime more generally.”

For years, Nigeria has been fighting to recover the stolen money, but companies linked to the Abacha family have gone to court to prevent repatriation. Deutsche, which banked Abacha’s money, has warned (paywall) 1,000 of its customers that they may also lose their accounts.

The Abacha case dates back to US enforcement efforts under the Obama administration, but the Crown Dependencies only need look at Britain’s Caribbean tax havens—known as the Overseas Territories—to understand the threat posed by Hodge and Mitchell.

3. FUJIMORI’S PERU: DEATH SQUADS, EMBEZZLEMENT AND GOOD PUBLIC RELATIONS

How does a former president get approval from two-thirds of his citizens while standing trial for human rights violations?

Peru’s Alberto Fujimori partly managed this by using over 75 per cent of the National Intelligence Service’s unsupervised budget to bribe politicians, judges and the media.

Peru’s former presidents are falling one by one and the Andean nation’s political class is teetering and spooked.

Fujimori presented a clean image to the public during his presidency while he used death squads to kill guerrillas and allegedly embezzled US$600 million in public funds.

After fleeing to Japan in 2000, he became the first elected head of state to be extradited to his home country, tried and convicted for human rights abuses.

With a sentence of more than 30 years in prison, Fujimori joins a long line of former Peruvian presidents who have been investigated or jailed for corruption.

4. KADYROV’S CHECHNYA: BIKERS, BOXERS, BRIBES

Imagine having to pay a bribe to keep your job. Chechens have to do exactly that, every month.

“Kadyrov stands above Russian law,” said Ilya Yashin, a liberal politician and Nemtsov’s political comrade. He, like many Russians, thinks of Kadyrov as a guard dog that has slipped his chain.

"Any attempt to remove him from his job, or to prosecute him, could provoke a new Chechen war. Putin is undoubtedly scared of such a development, which is why he can’t solve the Kadyrov problem,” Yashin further added

In Chechnya, everyone earning a wage pays an unofficial tax to an opaque fund controlled by the head of the republic, Ramzan Kadyrov.

While the fund helped build homes and mosques and provided international aid to Somalia, it also allegedly paid for Kadyrov’s lavish 35th birthday party and the celebrities that attended it, a US$2 million boxing session with Mike Tyson and 16 motorbikes that Kadyrov very publicly gifted to a nationalist biker gang.

Some Chechens lose half their income to this fund, which collects US$648 to 864 million a year, roughly the equivalent of two thirds of Chechnya’s budget. Kadyrov is also said to help himself to that national budget whilst committing human rights abuses that have led to sanctions from US authorities.

That is one explanation of why the leader of a region within Russia is able to act with such freedom. But it is not the only one, and not necessarily even the most likely.

If it were true, Putin might be keeping Ramzan at arm’s length, but he is not.

On the contrary: the president has said Kadyrov is like a son to him, while Ramzan says Putin is his idol. They meet regularly, converse warmly, praise each other.

Politically, there is little to separate them.

Indeed, Ramzanism is almost the ur-expression of Putinism: a philosophy that is equal parts bling, violence, nationalism, kleptocracy and religion.

5. Shutting down competition in Tunisia

There are no Big Macs in Tunisia.

That’s because the McDonald’s franchise was awarded to a business that didn’t have connections to the ruling family and the government stopped the fast food chain from entering the country.

From 1987 to 2011, President Ben Ali created laws that meant companies needed permission to invest and trade in certain sectors.

In the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution in 2011, some 550 properties, 48 boats and yachts, 40 stock portfolios, 367 bank accounts, and approximately 400 enterprises were seized from deposed President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali and his clan.

The Confiscation Commission in Tunisia estimates that the total value of these assets combined – the total worth of the Ben Ali clan’s belongings – was approximately $13 billion or more than one-quarter of Tunisian GDP in 2010.

This allowed him to shut competition out whilst letting 220 family businesses monopolise numerous industries, including telecommunications, transport and real estate.

In 2010, these businesses produced 3 per cent of Tunisia’s economic output, but took 21 per cent of the private sector profits.

How did they manage to drive up the profits of their firms to such astronomical levels? They did so by taking advantage of and manipulating Tunisia’s investment laws.

Ben Ali’s relatives flocked to sectors riddled with regulations; sectors such as telecoms, air and maritime transport, commerce and distribution, banking, real estate, and hotels and restaurants.

Entry restrictions to these sectors translated in greater market share, higher prices, and more money for the firms of Ben Ali’s extended family, who had privileged access. At the extreme, the rule in some sectors was Ben Ali or bust.

For instance, there was the failed entry of McDonald’s into Tunisia: After awarding the franchise to the “wrong” partner, entry was denied by the government and the franchise pulled its efforts to enter the Tunisian market altogether.

Over a 16-year period Ben Ali signed 25 decrees introducing new authorization requirements in 45 different sectors and new restrictions to foreign investment in 28 sectors - all benefits enjoyed by Ben Ali's family firms.

Ben Ali fled the country in 2011 and his assets were auctioned off, but few restrictive laws have been repealed, and questionably-connected firms with privileged access continue to reinforce and profit from inequality.

Tunisians paid a heavy price for this and missed out on employment opportunities, while new entrepreneurs and unconnected investors continued to fail.

6. UKRAINE’S MISSING MILLIONS

A golf course, ostrich farm, private zoo and full-size Spanish galleon replica were just some of the attractions at Mezhyhirya, the multimillion dollar 137-hectare estate of Ukraine’s former President Viktor Yanukovych.

The 345-acre presidential palace itself displayed the extent of his regime’s plundering: Yanukovych had built an estate so gaudy that it included a luxury car collection, an ostrich farm, and even a loaf of bread made of solid gold.

Also in the palace were reams of financial records revealing how Yanukovych and The Family moved state assets across the globe to offshore accounts and companies they controlled.

Among those companies was Davis Manafort Partners, a consulting firm that Yanukovych used to win elections and burnish his reputation.

Manafort, one of the firm’s owners, has been indicted for using the company to launder money. He has denied the charges in court.

Manafort is a “key witness” in three ongoing criminal probes in Ukraine: suspected money laundering by his former lobbying firm; a lucrative contract he steered toward the powerful American law firm Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom; and an investigation of the so-called black ledger, a document that reportedly shows illicit payments by the past regime.

While Ukrainian officials say Manafort holds important information that would help their investigations, the likelihood of him ever speaking with them is slim. He has been charged in the US by Mueller’s team and faces trial later this month, and is unlikely to be to questioned by Ukrainians during such a sensitive inquiry.

Yanukovych and his family fled to Russia in February 2014 after civil unrest sparked deadly conflict claiming over 100 lives, including by sniper bullets.

Three years after these tragic events, a Ukrainian court found Yanukovych guilty of high treason and sentenced him to 13 years in prison in absentia.

As he fled, Yanukovych left behind documents that showed how he financed a life of luxury at the expense of his citizens. Using nominees as frontmen in a complex web of shell companies from Vienna to London to Lichtenstein, Yanukovych allegedly concealed his involvement while syphoning off Ukrainian public funds for personal benefit.

In February, Swedish public broadcaster SVT reported that Yanukovych’s shell company with a Swedish bank account received a US$3.7 million bribe in 2011 and executed two transactions with a total worth of US$18 million in 2007 and 2014.

Former President Viktor Yanukovych and his associates allegedly made US$40 billion in state assets disappear. So far, the Ukrainian government has recovered just US$1.5 billion.

7. RICARDO MARTINELLI’S SPY-GAME IN PANAMA

Violation of privacy laws, embezzlement, abuse of authority and illicit association – former Panamanian President Ricardo Martinelli faces a variety of charges in his home country, after the United States extradited him in 2018.

While in office from 2009 to 2014, Martinelli allegedly rigged tenders for public contracts, including those for meals and school bags, under Panama’s largest social welfare scheme.

Most notably, he is accused of having used public funds to monitor the phone calls of more than 150 people, including politicians and journalists.

In total, he faces eight cases before the Supreme Court of Panama on charges related to his time in high office. These include allegations that he rigged tenders for public contracts for meals and book bags for schoolchildren under Panama’s largest social welfare scheme, the National Aid Programme.

Concerns have been raised that Martinelli has the financial means to flee the country in order to escape justice, as he has in the past. US Federal Attorneys in the United States emphasised the same message on multiple occasions during the extradition procedure - that Martinelli represented a flight risk.

Martinelli dismissed all of the allegations and charges against him as a ‘political vendetta’.

With his trial currently underway in Panama, he was banned from this year’s presidential elections, but promised to make a comeback and run for president in 2024.

8. THE 1MDB FUND: FROM MALAYSIA TO HOLLYWOOD

In 2009, the government of Malaysia set up a development fund, 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB). Chaired by the former prime minister, the fund was originally meant to boost the country’s economy through strategic investments. But instead, it seems to have boosted the bank accounts of a few individuals, including the former prime minister himself, a fugitive financier and a US rapper.

Authorities estimate that more than US$4 billion was embezzled in what is one of the world’s biggest corruption schemes, 1MDB. The fund has since been at the heart of one of the biggest corruption scandals in the world.

Through a network of shell companies and layers of transactions, billions of dollars of development money was allegedly spent on luxury real estate in New York, paintings and gifts for celebrities, among other things.

More than US$700 million may also be held in Razak’s private account, despite his claims that the money was a “donation” from a Saudi prince. Razak is currently facing charges for misappropriation of public funds.

How was the money spent?

Leaked financial documents allege that 1MDB was a hub of fraudulent activity from the outset. Vast sums were borrowed via government bonds and siphoned into bank accounts in Swizerland, Singapore and the US. Some $731m appeared in the personal bank account of Najib just ahead of the 2013 election, and is alleged to have been used to pay off politicians, his credit card bill and fund the lavish shopping habits of his wife. Najib denies the allegations and insists the money was donated by a Saudi prince.

It is alleged the fund bankrolled purchases including tens of billions of dollars’ worth of property in Beverly Hills and Manhattan, including an apartment once owned by Jay Z and Beyonce; a $35m private jet; a $260m yacht; a $3.2m Picasso given to Leonards DiCaprio; $85m in Las Vegas gambling debts; a birthday party for Low where Jamie Foxx, Chris Brown, Ludacris, Busta Rhymes and Pharrell Williams performed live and Britney Spears jumped out of a cake; and $8m in diamonds for Australian model Miranda Kerr.

In October, Najib was charged with six counts of criminal breach of trust over the theft and misspending of $1.59bn of government funds. Rosmah, Najib's wife, was arrested and charged with 17 counts of money laundering.

The couple pleaded not guilty to all charges.

9. THE RUSSIAN LAUNDROMAT (WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM MOLDOVA)

According to a recent study, more than one-fifth of Russia’s population lives in poverty, while 36 per cent are at risk of poverty. The Russian Laundromat, a massive money laundering scheme that siphoned off somewhere between US$20-80 billion in fraudulent funds away from public services and the citizens who need them most, could be one of the reasons why.

To move the money out of Russia, UK-registered shell companies issued fictitious loans to each other and Russian companies, fronted by Moldovan citizens, guaranteed them. Once the debtors failed to “pay back” these loans, corrupt Moldovan judges fined Russian companies and ordered them to transfer funds to accounts in a Moldovan bank. From there on, the money flowed into Latvia and other EU banks where it was ultimately cleaned.

Money to Play With

Money entered the Laundromat via a set of shell companies in Russia that exist only on paper and whose ownership cannot be traced. Some of the funds may have been diverted from the Russian treasury through fraud, rigging of state contracts, or customs and tax evasion. Money that might have helped repair the country’s deteriorating roads and ports, modernize the health care system, or ease the poverty of senior citizens – was instead deposited in a Moldovan bank.

At the other end of the Laundromat, money flowed out for luxuries, for rock bands touring Russia, and on a small Polish non-governmental organization that pushed Russia’s agenda in the European Union.

Well-known companies unwittingly took part when beneficiaries used their Laundromat money to buy goods and services.

South Korea’s Samsung received laundered money, as did the Swedish telecom company Ericsson, and the toolmaker Black & Decker.

Formal investigations are currently underway in several countries and the banks involved – Moldindconbank, Danske Bank, Deutsche Bank and HSBC – are in hot water for failing to comply with anti-money laundering rules.

10. SPAIN’S LARGEST CORRUPTION SCANDAL: GÜRTEL

Over the last 10 years, the Gürtel case has grown into to the biggest corruption scandal in Spain’s democratic history, reaching all the way up to the president’s office. At the centre, the complex scheme funnelled illicit donations and bribes to the then-ruling party in exchange for rigged government contracts.

If the name Gürtel doesn’t sound very Spanish to you, that’s no coincidence: it’s the German translation of the surname of the businessman at the heart of the scandal, Francisco Correa, meaning “belt” in English.

Correa eventually received a 51-year jail sentence, while a close ally and former treasurer of former president Mariano Rajoy was fined nearly US$50 million.

Peñas, a town councillor in a Madrid suburb, had worked with Correa for two years: they had started a political party together, to compete in local elections on an anti-corruption ticket. Peñas ran the campaign, Correa financed it.

But within a few months, Peñas had realised that his friend was corrupt: Correa’s real business was conspiring with local politicians to rig lucrative public contracts. Instead of confronting him – or turning him in – Peñas spent more than a year covertly gathering evidence against his boss.

After amassing hours of secret tapes, Peñas had finally gone to the police to report Correa for a series of crimes that threatened to land his former partner in jail for a very long time – along with a powerful cabal of corrupt politicians and businessmen.

The next day, he was called to meet Correa - a conversation which was also recorded by Peñas.

What Peñas would record that evening would become the key piece of evidence in the most far-reaching corruption scandal in Spain’s modern democratic history. The case would help shatter the nation’s two-party system, transform how the public viewed the people running the country and, eventually, bring down a government.

In the 12 years since Peñas began recording, Spanish voters’ confidence in their government has collapsed - taking down Rajoy's reign with it.

In June 2017, nine months after testimony began, one of the final witnesses took the stand: the prime minister, Mariano Rajoy. Although Rajoy was not accused of any crimes, it was a humiliating scene for him, the first sitting prime minister to be called to trial as a witness. Correa’s testimony and the evidence of Bárcenas’s ledger of payments in and out of the party slush fund had pushed him into a corner – among the names listed in that ledger was a certain “M Rajoy”. In a series of terse exchanges with a prosecution lawyer, Rajoy denied any knowledge of his party’s involvement in the scheme. He also denied knowing Correa or receiving off-the-book cash payments.

The court later said the testimony of Rajoy and others who denied knowing about the existence of the slush fund were “not credible”.

Within days of the verdict, the Socialist party Rajpoy lead - People's Party (PP) - called a no-confidence vote in Rajoy. On 31 May, with defeat seeming inevitable, Rajoy and his closest allies skipped out on the parliamentary debate about whether he should continue to lead the country. Instead, they went to a restaurant near the presidential palace, where they remained holed up for eight hours, reportedly eating sirloin steak and drinking whiskey while the press laid siege.

Within the decade, between Peñas going to the police and Rajoy’s downfall, the courts made slow progress, but public opinion shifted much faster. Before the crisis, satisfaction with the political system in Spain was among the highest in Europe, behind only Denmark, Luxembourg and Finland. After 2010, in the wake of austerity and endless corruption scandals, trust in institutions such as political parties and banks crumbled. Gürtel, like Watergate, has convinced many voters to take a conspiratorial view of politics.

In January 2019, Luis Bárcenas - then chief administrator of the party and later treasurer - told a court that several years earlier police, acting on orders of the interior ministry, had stolen documents in his keeping that allegedly proved former prime minister Rajoy had received off-the-books payments, an accusation Rajoy vehemently denies.

The scheme was discovered thanks to the help of Ana Garrido Ramos, a whistleblower who was also a key witness in this case, contributing to the collapse of the Rajoy government in June 2018.

11. VENEZUELA’S CURRENCIES OF CORRUPTION

Less than 20 years ago, Venezuela was South America’s richest country. Today, it’s facing one of its worst political and humanitarian crises – and corruption has a key role in it.

The plundering of the state-owned oil company, PDVSA, is exemplary of the widespread corruption at the highest levels of government. Once the basis of Venezuela’s wealth, the country’s vast oil reserves ultimately filled the pockets of a small group of individuals.

With help from European and US banks, a group of Venezuelan ex-officials allegedly siphoned off US$1.2 billion from PDVSA to the US, exploiting the country’s complicated currency exchange system that only allows certain people and companies to exchange currencies at the official, hugely inflated rate.

Officials bought Venezuelans Bolivars on the black market, at an exchange rate of ca. 1:100 (in 2014). That means they could have bought 100 million Bolivar for $1 million.

They then exchanged this money back at the official rate of 1:10, meaning they would get back $10 million – a tenfold increase.

Two people involved in the scandal pleaded guilty last year, and investigators are currently looking into more details of the money laundering scheme.

A number of prominent members of the Venezuelan elite were involved in the scheme. They played the country's currency system to gain money illegally – totaling $1.2 billion (€1.07 billion) in fraudulent sums.

Among them, according to US investigators, are Raúl Gorrín, a Venezuelan billionaire who owns the news network Globovision, and three stepsons of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, also referred to as "los Chamos." The three have not been indicted.

Playing Venezuela's currency exchange system

How did the embezzlement work? It took advantage of Venezuela's currency exchange rules.

There are two exchange rates in Venezuela: the national currency, the bolivar, and the US dollar.

The rate of the bolivar to the US dollar is fixed by the central bank.

But not everyone can convert bolivares into dollars, and vice-versa. Only a few companies can operate an official conversion from bolivares to dollars – including PDVSA.

All those who don't have access to official exchanges must operate on the black currency market, which has very different rates than the official ones.

Bolivares have a much higher value at the official exchange rate than at the black market rate – and the group of fraudsters reportedly exploited both the official and unofficial currency exchange systems.

12. THE PANAMA PAPERS

Following a huge leak from the Panamanian law firm, Mossack Fonseca, the Panama Papers exposed the darkest secrets of the financial secrecy industry.

The Panama Papers showed that Mossack Fonseca created 214,000 shell companies for individuals who wanted to keep their identities hidden. Behind the shell companies hid at least 140 politicians and public officials, including 12 government leaders and 33 individuals or companies who were blacklisted or on sanction lists by the United States government for offences like trafficking and terrorism.

Since the scandal erupted, several heads of government have resigned or faced prosecution, at least 82 countries launched formal investigations and Mossack Fonseca closed.

As a result of the Panama Papers, several countries committed to ending financial secrecy, with at least 16 countries or international bodies achieving at least one substantial reform and approximately 23 countries recovering at least US$1.2 billion in taxes.

The second leak of the Mossack Fonseca documents in August 2018 showed just how much the company scrambled to cover up violations of beneficial ownership transparency rules in the immediate aftermath of the scandal, Ukraine’s president Petro Poroshenko among them.

While the initial investigations into Mossack Fonseca by Panamanian authorities did not go far, in 2017 the firm’s two founders were arrested in Panama in connection to the Lava Jato corruption scandal, as part of an ongoing joint investigation with Brazilian prosecutors. In December 2018, the US authorities also charged four former employees of the firm.

European banks, who moved the dirty money of companies set up by Mossack Fonseca, are also increasingly being held liable for violating national and international anti-money laundering rules. Germany’s biggest bank, Deutsche Bank, which held accounts of shell companies owned by the convicted former Prime Minister of Pakistan Nawaz Sharif and his daughter, was raided in November 2018.

13. MALDIVES: A PARADISE LOST

In the Maldives, tourism is the largest contributor to the economy – it’s where the money is. So it should come as no surprise that the country’s biggest corruption scandal is also linked to tourism. In 2016, Al Jazeera revealed that approximately US$1.5 billion was laundered through fake tourism investments in a scheme of astounding simplicity.

The money was allegedly transported to the Maldives in cash, approved by the financial authority and transferred to private companies, where it appeared as clean profits from tourism investments.

That’s not the only case of dodgy tourism deals in the Maldives. Another scandal that came to light in 2018 saw more than 50 islands and submerged coral lagoons leased out to tourism developers in no-bid deals. At least US$79 million from the lease fees was embezzled into private bank accounts and used to bribe politicians. The scandal implicated local businessmen and international tourism operators as well as former president Abdulla Yameen, who allegedly received US$1 million in funds.

The allegations of high-level corruption arrived just before the Maldives held presidential elections, on September 23. Early ballot counts indicate that President Yameen lost power to the opposition candidate by a margin of 16.7 per cent. Voting on Sunday took place amidst claims of harassment of opposition parties

Just days before the election, investigative journalists at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) used leaked cell phone and email data from former Vice President and Tourism Minister Ahmed Adeeb (now imprisoned on charges including corruption and terrorism), public documents, and internal government records, to discover which hotels are implicated in the scandal.

Outgoing President Yameen has denied any involvement in misappropriating money paid for island leases.

14. TEODORÍN OBIANG’S #LUXURYLIVING IN EQUATORIAL GUINEA

Teodorín Obiang’s Instagram account celebrates #LuxuryLiving, showing off his mansions, million dollars’ worth of Michael Jackson memorabilia and supercars. However, Obiang funds this lifestyle by embezzling funds from Equatorial Guinea where he serves as vice president to his own father.

This oil-rich country has the highest per capita income in Africa, but about three-quarters of its population lives in poverty. Since 1979, the ruling Obiang family, along with their cronies, have stolen billions of dollars from the people.

As the most conspicuous and international spender in this kleptocracy, justice caught up with Teodorín Obiang several times. In 2014, the US Department of Justice prosecuted him for money laundering and seized US$30 million worth of assets. In 2017, French authorities found him guilty of embezzlement and confiscated his assets worth US$35 million, while Switzerland seized 24 of his supercars. This is some progress, but still a drop in the ocean compared to the flood of ill-gotten money that has flowed out of the country.

The US Department of Justice prosecuted him for money laundering, and it estimated his global assets at US$300 million. That case settled with Teodorin forfeiting US$30 million, but he will go on trial in France next week for allegedly laundering $196 million. Switzerland has also just launched an investigation against him, seizing a bunch of supercars and a US$100 million yacht. He also spent almost US$1 million on Michael Jackson memorabilia, including US$275,000 on a Bad Tour glove.

15. HOW THE GUPTA FAMILY CAPTURED SOUTH AFRICA THROUGH BRIBERY

In what’s been described as a “modern coup”, the Gupta family took control of South Africa.

Through allegedly bribing politicians, giving lucrative jobs to President Zuma’s children and other ways of buying influence, Ajay, Atul, and Rajesh Gupta captured the state.

The three Gupta brothers had bought the Optimum Coal Mine in December 2015, adding it to the tentacular empire they were building across South Africa, with interests in uranium deposits, media outlets, computer companies, and arms suppliers.

The miners would watch as the Guptas landed their helicopter in the parched soccer field with its rusty goalposts, only to swagger around with their gun-toting white bodyguards and take their kids to the mine vents without protective gear.

Sometimes, when the brothers were in a magnanimous mood, they would dole out fistfuls of cash to miners who had been particularly obsequious that day.

At the same time, they cut corners viciously. Health insurance and pensions were slashed. Broken machines were patched up with old parts from other machines. Safety regulations were flouted.

The Gupta family took as much as US$7 billion in government funds, including a US$4.4 billion supply contract with South Africa’s rail and port company.

The Guptas also hired and fired government ministers, while the president fired tax officials and intelligence chiefs to protect them from investigation.

In 2016, when a deputy minister went public about the US$45 million that the Gupta family offered him to fire treasury officials, the Guptas fled the country.

President Zuma has since lost government office and faces corruption and money laundering charges.

Tragically, the scandal has also inflamed racial tensions in a country still struggling to recover from decades of apartheid. Indians, who came to South Africa under British rule in the 1860s as indentured laborers and traders, played a prominent role in the country’s anti-colonial and anti-apartheid struggles.

In the meantime, South Africa’s economy struggles and the country continues to face high levels of inequality.

16. LEBANON’S GARBAGE: THE STENCH OF CORRUPTION

Sometimes dirty money can lead to filthy cities. Since 2015, Lebanon has had a garbage crisis that’s seen streets and beaches covered in rubbish bags, extreme stench and water contamination.

This threat to public health came about when Beirut and Mount Lebanon’s main waste disposal company, Sukleen, stopped collecting garbage.

The company – which had a monopoly since the 1990s – was forced to close an overflowing landfill which was used for 12 years longer than scheduled.

Lacking the infrastructure to dispose of the garbage elsewhere, the company let the rubbish bags pile up.

Two months on, the government has still failed to replace Sukleen. Six private firms, also connected to the ruling elite, failed to win the contract to remove rubbish because the fees they quoted turned out to be much higher than Sukleen.

As mounds of rubbish steam in the heat and humidity of the Lebanese summer, the broad-based movement of civic protest in the streets has taken aim at politicians that provoked a popular movement called “You Stink”, which called for the government to clean up its streets and its corruption problems.

Tammam Salam, the Sunni Muslim prime minister, said that serious as it, the uncollected waste is merely a manifestation of the “political garbage” crisis afflicting Lebanon.

How did a single company monopolise a key public service?

It had strong connections with two of Lebanon’s prime ministers. Lebanon also has a culture of patronage, where government contracts are often won through political connections and bribes.

17. FIFA’S FOOTBALL PARALLEL UNIVERSE

The indictments on 27 May 2015 of nine current and former Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) officials on charges of racketeering and money-laundering changed the sporting landscape overnight.

Suddenly a system of “rampant, systemic and deep-rooted corruption” was brought starkly into global focus.

The surprising re-election of FIFA president, Sepp Blatter, who presided over a culture of impunity, exposed just how much football exists in a parallel universe without accountability.

It is easy to understand why public trust in FIFA fell to an all-time low.

In 2017, Transparency International and Forza Football, a football fan opinion platform with more than 3 million subscribers, completed a survey of 25,000 fans from over 50 countries to find out what they thought.

At the time, 53 per cent of fans had no confidence in FIFA and only a quarter of fans globally thought that newly reelected president, Gianni Infantino, restored trust in FIFA.

"If we really want sport to be the basis for a better society, to be one of the pillars for human and social development, we need to rethink the rules of sports governance and their criteria of representation and accountability – and build something new, transparent and committed," said Raí Souza Vieira de Olivera, captain of the Brazilian 1994 World Cup winning team.

The Global Corruption Report: Sport looks at what has gone so badly wrong and what can be done to fix it. It examines the structures of sport, presents examples of good and bad practice and provides a platform to the various voices in the multi-billion dollar business that sport has become: including the often overshadowed views of athletes and fans.

The report is divided into key sections covering:

► governance

► major sporting events, including the Olympics and the World Cup

► match-fixing

► money, markets and private interests in football

► US college sports

► the role of participants in sport

The report is a resource for all those interested in restoring trust in sport. We encourage international, regional and national sports organsiations, sponsors, local and national government, and international organisations to review its detailed recommendations and work together with supporters and the grassroots to #cleanupsports.

Extracts from the report can be found here. It includes articles from 60 experts and more than 15 country specific reports.

18. MYANMAR’S DIRTY JADE BUSINESS

Myanmar is a tragic example of how rich natural resources are often exploited by the corrupt while causing social and environmental disasters that affect ordinary people.

In 2015, a report revealed that corrupt military officials, drug lords and their cronies, had been illegally exploiting jade mines in northern Myanmar and smuggling the stones to China.

In total, more than US $31 billion in jade stones were extracted in 2014 alone – the equivalent of half of Myanmar’s GDP that same year. Yet, the majority of people living in the mining regions and working in the mines did not see any of this money and as much as US$6.2 billion was lost in taxes.

At the same time, areas rich in jade have been shaken by armed conflicts, while aggressive exploitation has led to environmental damages and mining accidents that have cost hundreds of lives. Despite efforts of the Myanmar governments to reign in the illicit jade business, mining still poses a serious risk to the environment and the people living in the region.

19. FIGHTING IMPUNITY IN GUATEMALA

Approximately 90 per cent of crimes in Guatemala go unpunished, so taking action against impunity should be a priority.

At least that’s what the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), backed by the UN, has been doing successfully for the past 12 years.

In 2015, thanks to the efforts of the CICIG, the former president of Guatemala was forced to resign because of a corruption investigation that ultimately led to his conviction.

Since then, the commission has been investigating dozens of high-level corruption cases and enjoys strong popular support.

Jimmy Morales, a stand-up comedian who ran for president in 2015 with the slogan “Not corrupt, nor a thief,” is accused of campaign finance violations.

For months, Guatemalan President Jimmy Morales tried to stop the UN-backed anti-corruption investigation into his government.

But when the CICIG started investigating current president Jimmy Morales and his family in 2017, Morales unilaterally revoked the agreement with the UN which underpins the ability of the CICIG to operate in the country.

Over the past years, the president has been leading a fight against anti-corruption efforts in Guatemala, ignoring rulings of the Guatemalan Constitutional Court.

Last September, Jimmy told CICIG investigators they were no longer welcome in Guatemala and denied a visa to lead prosecutor Ivan Velasquez.

The courts quickly ruled that Ivan must be allowed to re-enter Guatemala to continue his work, but the president refused.

On January 6, immigration officers sent by Jimmy arrested Ivan’s deputy prosecutor at the Guatemala City airport. The Constitutional Court ordered his release and reiterated that the government must let the CICIG continue its investigation.

Instead, Guatemala’s solicitor general began impeachment proceedings against three of the court’s five justices, saying they had exceeded their authority by ruling on foreign affairs issues.

The global consequences of Guatemala’s constitutional crisis will go well beyond its borders.

More undocumented migrants have been detained crossing the United States’ southern border come from Guatemala than from any other country.

The collapse of its democracy would surely send even more desperate residents fleeing.

El Salvador, the most violent Central American country, is hoping to do the same soon.

Guatemala’s crisis weakens these international partnerships. If a president can terminate an investigation when it threatens his power, can justice ever really be served?

20. TURKEY’S “GAS FOR GOLD” SCHEME

In a real-life version of House of Cards, Turkey found itself embroiled in a massive corruption scandal in 2013.

Turkish police officers raided several homes, including two belonging to the families of the ruling Turkish elite.

During the investigation, police confiscated some US$17.5 million in cash, money allegedly used for bribery.

At the heart of the scandal was an alleged “gas for gold” scheme with Iran, involving businessman Reza Zarrab - who was reportedly involved in a money laundering scheme as part of a strategy to bypass UStates-led sanctions on Iran.

All the 52 people detained that day were connected with the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP).

Prosecutors accused 14 people - including Zarrab and several family members of cabinet ministers - of bribery, corruption, fraud, money laundering, and gold smuggling.

The whistleblowers who tipped off the police claimed that the son of then Prime Minister (now President) Recep Tayyip Erdogan was next in line.

President Erdoğan remains defiant about the scandal, dismissing or reassigning thousands of police officers and hundreds of judges and prosecutors, including those leading the investigation, and passed a law increasing government control of the judiciary.

21. THE AZERBAIJANI LAUNDROMAT

Some governments make genuine efforts to improve their human rights records and strengthen democracy. Others may try to clean up their reputation by bribing foreign politicians.

Azerbaijani leaders allegedly bribed the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) delegates to talk up Azerbaijan’s human rights record and water down critical election monitoring reports.

In September last year, a massive leak of bank records from 2012 to 2014 showed that the ruling elite of Azerbaijan ran a US$2.9 billion slush fund and an international money laundering scheme. Part of the money was used to help whitewash Azerbaijan’s international image, which had been rightly tainted due to grave human rights violations.

At the heart of the scandal was the Council of Europe, an organisation of 47 member states including Azerbaijan, dedicated to protecting human rights and upholding rule of law in Europe.

While real accountability is yet to come for the culprits that undermined Europe’s core human rights organisation, there have been some consequences.

An independent PACE investigation found several delegates engaged in corrupt and unethical behavior, resulting in sanctions for these individuals.

Transparency International Germany also recently filed a criminal complaint against German MPs who allegedly took bribes.

Danske Bank is under investigation for this and other money laundering scandals, and was forced to shut its branch that handled the dirty money.

All leaders dealing with Azerbaijan must show a principled approach and put human rights on the agenda of every conversation.

Moreover, politicians who allegedly took bribes from the Laundromat must be investigated and held accountable for their actions.

22. PARADISE PAPERS: WHERE THE RICH & POWERFUL HIDE THEIR MONEY

Countries lose around US$500 billion per year in corporate tax and further billions from individuals. That’s enough to pay for the UN’s aid budget twenty times over and bring many nations out of poverty.

In 2017, a major investigation exposed a vast, secret parallel financial universe based on a huge leak of documents from the Bermuda-based elite legal firm, Appleby.

Dubbed the Paradise Papers, the investigation shed light on the widespread use of secretive tax havens by 120 politicians, royals, oligarchs and fraudsters.

The “Paradise Papers,” the latest in a series of global journalistic exposés of the offshore financial industry, has triggered tax-related investigations by governments around the world - from the Netherlands to Vietnam to New Zealand.

The series of investigation shows how corporations use these havens to reduce their taxes drastically, and in some cases, commit crimes. For example, offshore secrecy put the commodities giant, Glencore, in a position to bribe the former president of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Joseph Kabila, while it negotiated for mining licenses.

Based on yet another mass data leak, the Paradise Papers sparked new or expanded criminal investigations in Switzerland and Argentina, accelerated sweeping reforms by the European Union, triggered a wave of audits in India and South Korea and sparked political uproar in Turkey and Angola.

“The Paradise Papers show the magnitude of the exploitation,” the San Francisco Chronicle declared in an editorial.

“It’s a maddening reality for the rest of us who pay our fair share of the cost of public services.” stated the newspaper.

The leak helped expose this and other criminal investigations, accelerated EU action against tax havens and inspired citizens around the world to demand an end to the paradise havens that make life difficult for ordinary citizens.

23. OPERATION LAVA JATO: CLEAN CARS, DIRTY MONEY

There’s graft, and then there’s Odebrecht graft.

By late summer 2015, the men running bribery at the Brazilian construction giant Odebrecht SA were plotting another operation—not to rig a contract, which was their bread and butter, or to meddle in the politics of a sovereign nation, as they’d done on many occasions, but this time to save themselves.

What began in 2014 as the Lava Jato investigation, or “Operation Car Wash”, involving a network of more than 20 corporations – including Brazilian oil and construction giants, Petrobras and Odebrecht – has since grown into one of the biggest corruption scandals in history.

This case has it all: dirty money, foreign bribery, illicit financing of political parties, criminal networks, fraudulent business executives, crooked politicians and a system of corruption embedded so deeply within Brazilian politics and business that exposing one piece started a chain reaction.

They did it by creating fake engineering, construction, and consulting companies that used secret bank accounts to pay fake invoices submitted by fake customers.

Often these people were politicians—the company had been bankrolling campaigns in Brazil, including presidential campaigns, going back to when bribery was strictly a cash business.

Since the establishment of Structured Operations, Odebrecht had funded plots to elect a half-dozen presidents in Latin America; buy the friendship of heads of state in Angola, Peru, and Venezuela; and pay off hundreds of legislators from Panama to Argentina.

Involving nearly US$1 billion in bribes and more than US$6.5 billion in fines, it’s difficult to find a region of the world unaffected by Lava Jato’s reach.

The case extends across at least 12 countries in Latin America and Africa, more than 150 politicians and business people convicted in its wake, including one president, and indirectly, two successors. And the allegations keep coming.

24. ANDREJ BABIŠ’S CONFLICT OF INTEREST IN CZECHIA

In early June 2019, almost thirty years after peaceful protests led to the fall of communism in former Czechoslovakia, more than 120,000 citizens marched in Praguepeople in Prague, Czechia.

This time, they were calling on Prime Minister Andrej Babiš to resign.

The protests gathered momentum after the European Commission (EC) confirmed that Babiš had significant conflicts of interest regarding his private businesses.

The EC was following a complaint from our national chapter in Czechia, which revealed that one of the Prime Minister’s many companies, Agrofert, had received more than US$19 million in EU agricultural subsidies.

In 2017, Babiš put the company into two trusts, but remained the ultimate beneficiary of these funds, hiding behind an additional layer of secrecy.

The following year, TI-CZ revealed that Prime Minister Babiš was a controlling entity of Agrofert, a Czech company that operates in agriculture, construction, logistics and other sectors.

As the sole beneficiary of two trust funds that own 100 per cent of the shares of Agrofert, Babiš received millions of euros in EU subsidies each year.

Two years later, TI-CZ filed a complaint with the Czech authorities concerning the prime minister’s conflict of interest in relation to media ownership.

As part of its many holdings, Agrofert owns a publishing company called MAFRA.

However, Czech law prohibits government ministers, including the prime minister, from owning or controlling any media outlets.

Later, in September 2018, TI-CZ sent a complaint and open letter to the European Commission concerning Babiš’s conflict of interest as a beneficial owner of Agrofert.

As a result, in December 2018, the European Commission suspended subsidies to Agrofert and last Friday, after a thorough review of the case, the EC confirmed that Prime Minister Andrej Babiš maintains significant conflicts of interest.

In addition, in January 2019, Czech authorities found the prime minister had a conflict of interest in relation to his media holdings.

Babiš appealed and Czech authorities are currently reviewing the case again. TI-CZ urges Czech authorities to take into account the EC’s recent decisions regarding this case.

In Czechia, “beneficial owners” like Babiš are not publicly known, but in neighbouring Slovakia, owners must disclose who they really are when bidding on public contracts.

Thanks to Slovakian law and some good detective work from TI Czech Republic, the EU recently ruled that Agrofert must repay the money it took from taxpayers over the past two years.

25. THE TROIKA LAUNDROMAT

Half of Russia’s wealth is allegedly stashed in offshore tax havens.

The Troika Laundromat investigation, launched by the Organized Crime and Corruption Project (OCCRP) and 20 media partners, shines a spotlight on a cast of new and familiar characters in the ongoing saga surrounding flows of dirty money through the world’s financial system.

Leaked data from Troika Dialog – once Russia’s largest private investment bank – shows that the bank created at least 75 shell companies in tax havens around the world. When opening accounts in European banks – such as now-defunct Ukio bankas in Lithuania, Raiffeisen in Austria and Commerzbank in Germany – who happen to be the real owners.

The findings draw on a massive - possibly the largest ever - leak of bank records, emails and contracts. Investigative journalists sifted through 1.3 million bank transactions between 233,000 companies and individuals, with a total value over US$470 billion, dated between 2006 and 2012.

At the centre of the investigation is Troika Dialog, a private Russian investment bank set up in the 1990s that was acquired by state-owned Sberbank in 2012. Troika’s stated objective was to attract foreign investors to Russia. But, as the leaked bank records reveal, it did more than just that.

How it worked:

Troika Dialog created the 75 shell companies that were registered in tax haven jurisdictions like the British Virgin Islands.

The companies were further incorporated within shell companies in other tax haven jurisdictions.

When opening bank accounts, the real owners hid behind unknowing proxies such as Armenian seasonal workers in Moscow.

These shell companies issued, cancelled and paid for contracts, invoices, and loans – all with fake paperwork of unwitting Armenian seasonal workers behind which the real owners hid.

Some of this money flowed out of the Troika Laundromat and into the global financial system as clean cash.

As a result, Russian oligarchs and politicians secretly acquired shares in state-owned companies, bought real estate both in Russia and abroad, purchased luxury yachts and hired music superstars for private parties.

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel